Frequently Asked Questions

The Offshore Infrastructure Regulator works to provide accurate information about the offshore renewables industry, and promotes leading work health and safety, infrastructure integrity and environmental management practice.

The Offshore Infrastructure Regulator

Accordion: What is the role of the Offshore Infrastructure Regulator?

This whole section will be converted into an accordion. Use basic block if you need spacer.

Established under the Offshore Electricity Infrastructure Act 2021 (OEI Act), the Offshore Infrastructure Regulator (OIR) has responsibility for operational oversight of the offshore renewables industry with particular focus on work health and safety, infrastructure integrity and environmental management.

Specifically, the OIR is responsible for overseeing activities involving the construction, installation, commissioning, operation, maintenance or decommissioning of offshore renewables energy infrastructure from three nautical miles from the coast to the boundary of Australia's exclusive economic zone. Coastal waters remain the responsibility of the adjacent state and Northern Territory governments.

The OIR has functions to promote and provide advice to stakeholders, assess risk management plans, conduct inspections to monitor compliance, investigate to verify and learn from non-compliance, take enforcement action to correct and deter non-compliance fostering continuous improvement in industry performance.

The role of the OIR formally commences once the Minister for Energy has granted a licence under the OEI Act.

Licensing

Accordion: Does the Offshore Infrastructure Regulator award licences?

This whole section will be converted into an accordion. Use basic block if you need spacer.

No. The Offshore Infrastructure Regulator does not award licences.

Under the Offshore Electricity Infrastructure Act framework, the Offshore Infrastructure Registrar (the Registrar) is responsible for administering the licensing scheme, including assessing licence applications and making recommendations to the Minister for Energy on offer and grant of licences.

The Registrar's assessment is merit-based and includes an assessment of technical and financial capability, the viability of the proposed project, whether the project is in the national interest and the suitability of the person to hold a licence. Further information about roles and responsibilities of the Registrar is available here.

Accordion: Can a developer do any site investigation work prior to being granted a licence under the Offshore Electricity Infrastructure Act?

This whole section will be converted into an accordion. Use basic block if you need spacer.

Yes. A prospective developer can progress non-invasive site investigation works that do not involve the deployment of offshore renewable energy infrastructure or offshore electricity transmission infrastructure (e.g. environmental surveys, vessel-based surveys) without a licence or consent under the Offshore Electricity Infrastructure Act 2021. Other laws such as the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) still apply.

Information about the requirements of the EPBC Act is available on the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water’s website.

Accordion: Does the granting of a feasibility licence under the OEI Act mean that an offshore wind farm will be constructed?

This whole section will be converted into an accordion. Use basic block if you need spacer.

No. The purpose of a feasibility licence is to allow the licence holder to assess the feasibility of a proposed offshore infrastructure project, such as a commercial offshore wind farm, within the licence area.

The feasibility of an offshore wind farm project will depend on a range of technical, environmental, commercial, socioeconomic and other factors that will determine whether a particular project is viable in a particular location.

Assessing the feasibility of an offshore wind farm will require the licence holder to carry out a variety of studies and investigations necessary to reduce uncertainties and risks and determine whether it is feasible to progress to a full-scale commercial project.

For example, feasibility studies would include assessing the physical conditions of the seafloor to determine what foundation designs might be suitable. They will also include studies to assess a proposed project’s commercial viability.

Assessing feasibility also covers the work needed to understand the environmental setting for a proposal, the nature and scale of its potential environmental impacts and the management measures that will need to be put in place to control those impacts so they remain acceptable and comply with the law.

The term of a feasibility licence (7 years) is when the licence holder is expected to have the environmental impacts of their proposed project assessed in accordance with the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act).

The EPBC Act formal assessment process affords the public several opportunities to make comments on the project and its environmental impacts and management. The final decision whether or not to approve the proposal under the EPBC Act is made by the Federal Minister for the Environment.

Once this approval is obtained the feasibility licence holder may then prepare a management plan for the project and apply for a commercial licence under the Offshore Electricity Infrastructure Act 2021.

The final decision to grant a commercial licence and allow a windfarm to be constructed is made by the Federal Minister for Climate Change and Energy.

Further information about feasibility licenses is available on the Registrar’s website.

Management plans

Accordion: What is a management plan?

This whole section will be converted into an accordion. Use basic block if you need spacer.

A management plan is a legally enforceable document that details how activities are to be carried out under an Offshore Electricity Infrastructure Act (OEI Act) licence.

Before a licence holder can commence activities that involve the construction, installation, commissioning, operation, maintenance or decommissioning of infrastructure in the Commonwealth offshore area they must have a management plan approved by the Offshore Infrastructure Regulator (OIR).

Management plans should be developed in consultation with stakeholders and set out how a licence holder intends to manage work health and safety, infrastructure integrity and environmental management risks.

The content requirements for management plans are set out in the Offshore Electricity Infrastructure Regulations 2022. Contents of a management plan will vary according to the licence and type of project.

Accordion: Can a management plan cover activities under different licences?

This whole section will be converted into an accordion. Use basic block if you need spacer.

Yes. There is nothing from a regulatory perspective that would inhibit the submission of a single document as a management plan application for two licences (e.g. a transmission infrastructure licence and a commercial licence) provided those licences are held by the same licence holder.

Approval by the OIR would indicate that the approved management plan is the management plan in force for both licences.

Where a licence holder intends to submit a single document for approval of activities under two licences, this should be made clear to the OIR in the management plan application.

Accordion: Can a management plan cover activities to be conducted under a licence that has not yet been granted?

This whole section will be converted into an accordion. Use basic block if you need spacer.

No. The granting of a licence and approval of a management plan are distinctly separate processes with different decision makers under the Offshore Electricity Infrastructure Act framework.

Once an OEI licence has been granted by the Minister for Climate Change and Energy, the licence holder can submit a management plan to the OIR for assessment.

The granting of a licence represents the formal commencement of the OIR’s operational regulatory role.

Environmental management

Accordion: Can fishing coexist with offshore wind?

This whole section will be converted into an accordion. Use basic block if you need spacer.

A key principle of the Offshore Electricity Infrastructure Act (OEI Act) Framework is coexistence with other users of the marine environment.

International experience shows that the offshore renewables sector can co-exist with other offshore industries and activities, with many examples of fishing continuing in and around operational offshore wind farms. There are also examples where the introduction of offshore renewables has led to changes in fishing areas and activities.

Effective liaison between offshore renewables proponents and fisheries stakeholders is important to understand the interactions between the sectors and to identify, avoid and mitigate any potential impacts such as displacement of fisheries.

The best time to explore options for coexistence with fisheries is during the feasibility licence phase of a project while licence holders are considering early design and project layout. During this phase considerations such as fisheries access, nature inclusive design and the safety of workers and fishing vessel operators can be considered together and contribute to design decisions.

In addition, the OEI Act provides for safety and protection zones to be established in and around offshore renewable energy projects. A safety zone can prohibit vessels from entering a specified area for a period of time, such as during construction of a wind farm, to minimise risks to the safety of workers and to other users of the marine environment. A protection zone can prohibit or restrict vessels from conducting certain types of activities which may result in risks to safety or damage to offshore renewable energy infrastructure or offshore electricity transmission infrastructure.

The exact details and duration of safety and protection zones will be determined on a project-by-project basis by the Offshore Infrastructure Regulator. The OIR will seek to ensure that offshore infrastructure is appropriately protected without unreasonably restricting the movements of transiting vessels in accordance with international obligations. Safety and protection zones can only come into effect at the commencement of installation activities.

Licence holders will be expected to carry-out appropriate consultation with potentially impacted marine users in the course of preparing safety and protection zone applications.

Accordion: How far off the coast are most offshore wind farms and will they be visible from the shore?

This whole section will be converted into an accordion. Use basic block if you need spacer.

The visibility of offshore wind infrastructure depends on a range of factors including the size of the turbines, weather conditions, distance of the wind farm to shore and the curvature of the Earth.

In Australia, all current and proposed declared areas in Commonwealth waters that would allow wind farms to be constructed in the future are at least 10 kilometres from shore at the closest point. These setbacks from the coastline have been applied to reduce visual amenity impacts to coastal communities.

States and territories make decisions about deployment of renewable energy infrastructure within the first 3 nautical miles (~5.5 km) from shore. To date no State or Territory jurisdictions have approved construction of wind turbines this close to shore.

Areas proposed for offshore wind in Australia are subject to a statutory consultation process, providing an opportunity for coastal communities to have their say on the suitability of prospective areas. The process for identifying and assessing areas for offshore wind development is led by the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water and further information about the process is available on the Department’s website.

Accordion: What are the benefits of offshore wind compared to onshore wind?

This whole section will be converted into an accordion. Use basic block if you need spacer.

Offshore wind farms have higher capacity factors compared to onshore wind farms thanks to higher, more consistent wind speeds

Whilst building wind farms onshore can reduce challenges and costs associated with operating in the marine environment, there are transport and logistical constraints which limit how large individual turbines and related infrastructure can be.

Other factors such as competing land uses, socioeconomic and environmental impacts, proximity to markets and generally lower and less consistent wind speeds limit the potential size, generation capacity and efficiency of onshore wind installations.

Taking wind offshore reduces or removes many of these constraints allowing wind farms to be scaled-up to generate more energy, more efficiently, with fewer installations. These benefits, combined with access to more reliable and consistent wind speeds and reducing costs means that offshore windfarms are becoming increasingly competitive in the global energy market. In some locations, offshore wind has already become the most cost competitive option for new generation with further efficiencies expected from economies of scale and future innovation.

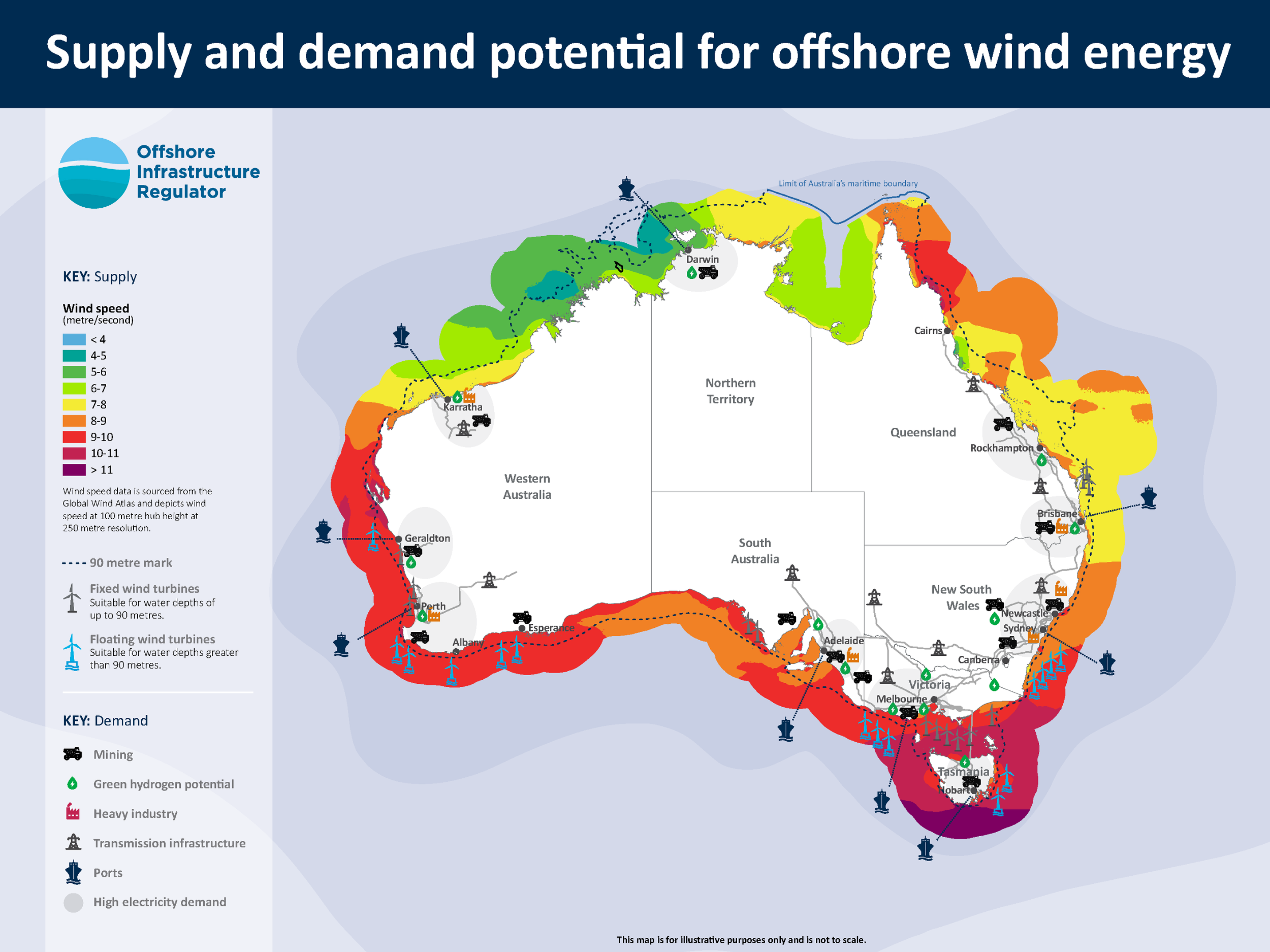

Australia’s most prominent offshore wind resources are in the southern half of the continent as shown in our supply and demand potential for offshore wind energy map.

Accordion: Are there any differences between the nature of marine surveys conducted for offshore wind and offshore petroleum?

This whole section will be converted into an accordion. Use basic block if you need spacer.

Yes. Marine seismic surveys commonly undertaken for offshore oil and gas are distinctly different to geophysical investigations conducted for offshore wind.

Seismic surveys for oil and gas are larger in scale and use larger vessels that tow longer equipment through the water emitting higher intensity sound. These surveys assist in building an understanding of hydrocarbon reservoirs within deep geological layers beneath the seafloor.

Geophysical investigations for offshore windfarms use smaller vessels and smaller equipment that emit lower energy levels. Equipment used in geophysical investigations for offshore wind typically include multi-beam echo sounders, sub-bottom profilers, side scan sonar, magnetometers and underwater cameras.

Geophysical investigations for offshore wind are conducted to gather information about a project area such as the features and composition of the seabed where developers plan to install infrastructure. Geophysical investigations are also used to identify any archaeological features, abandoned structures or significant habitat that needs to be considered during design and construction of the wind farm.

Unlike equipment used for oil and gas seismic surveys, geophysical investigations for offshore wind use equipment deployed on or at short distances behind the vessel that use low energy acoustic levels, propagated over shorter ranges. Therefore, this technology has a lower impact to marine life. Comparable equipment is used on commercial ships, fishing vessels, research vessels and recreational boats to visualise the make-up of the seafloor and detect fish.

The most common approaches to reduce impact to marine life from any offshore surveys (seismic or geophysical) are to schedule surveys to avoid times when interactions are likely to be high, move vessels at low speed, maintain trained observers for marine life throughout the survey and power down or cease the survey if animals approach the vessel.

The impact of oil and gas seismic surveys to marine life is a continuing topic of academic research, providing critical information to industry, policy makers and governments. There is a large body of international and Australian scientific research into the interaction of seismic surveying on marine life, including the effect of underwater sound generated from different marine survey techniques. Research demonstrates that, when properly managed, noise levels from seismic exploration surveys do not cause environmental harm. Geophysical investigations for offshore renewables commonly use surveying technologies that produce acoustic energy levels that are below the level researched in academia or by the exploration industry.

Accordion: Do offshore wind farms have the potential to disturb marine fauna?

This whole section will be converted into an accordion. Use basic block if you need spacer.

Yes, just like all human activities, offshore wind farms have effects on the natural environment, including marine fauna.

The nature and extent of potential environmental impacts of an offshore wind farm is dependent on a range of factors. These factors include the proposed location of infrastructure, the windfarm design and technology adopted, construction and operation methods, as well as specific management arrangements that will be in place.

During construction and operation offshore wind farms create noise, which has potential to affect the behaviours of marine fauna like whales and fish.

The physical presence of an offshore wind farm has potential to alter natural patterns of movement and behaviour in marine fauna or can deter them from using areas. This may include effects on migratory patterns or habitat utilisation for activities like breeding or foraging in marine mammals and birds.

Artificial lighting associated with offshore wind farms for navigational safety may have implications for natural behaviours of sensitive species including birds and marine turtles.

Developers are expected to avoid and minimise the potential for disturbance to marine fauna when planning their offshore wind project. Impact avoidance and minimisation may be achieved by adopting measures associated with project siting, technology selection, infrastructure design and activity scheduling.

The Department of Climate Change, Energy the Environment and Water is responsible for environmental assessments and approvals for offshore wind farm projects. Any offshore renewable energy activity that is likely to have a significant impact on a nationally protected matter must undergo an environmental assessment under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) and receive an approval before it can go ahead. Further information about the EPBC Act assessment process is available on the Department’s website.

The Department has also developed guidance on key environmental factors for consideration when developing offshore renewables projects in the marine environment.

As the global offshore wind industry continues to evolve, developers are increasingly investigating nature-inclusive solutions in offshore wind farm design to minimise impacts on nature and enhance the diversity of marine life.

Financial security

Accordion: What is the process to provide financial security?

This whole section will be converted into an accordion. Use basic block if you need spacer.

The OEI Act requires licence holders to provide financial security to the Commonwealth before any offshore renewable energy infrastructure or offshore electricity transmission infrastructure can be installed.

The licence holder must provide financial security directly to the Commonwealth (the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water [DCCEEW]). The OIR does not receive, hold or return financial security on behalf of the Commonwealth.

DCCEEW has published guidance on the process for proving financial security to the Commonwealth: Provision of financial security to the Commonwealth - DCCEEW

| Role of the OIR | Role of DCCEEW |

|---|---|

|

|

Accordion: Can partial release of financial security be considered?

This whole section will be converted into an accordion. Use basic block if you need spacer.

This will depend on how a licence holder has set out their arrangements for provision of financial security to the Commonwealth in their management plan.

For example, if a licence holder has separate securities for particular licence infrastructure or activity campaigns such as metocean and geotechnical investigations, releasing securities by activity completion may be facilitated by the Department of Climate Change, Energy the Environment and Water.

Accordion: What evidence should licence holders gather to support the return of financial security?

This whole section will be converted into an accordion. Use basic block if you need spacer.

Licence holders may provide daily logs, photos, daily operational reports, equipment inventories or records from contractors to demonstrate to the OIR that relevant structures, equipment and property have been removed from the licence area.

In deciding whether to reduce or release financial securities the Minister must seek advice from the OIR. Compliance information provided by licence holders will form the basis for OIR's advice to the Minister.